#21: How Running Is Changing the Way I Feel

one step at a time

Welcome to Homebody Stories! A newsletter offering reflections from an ex-productivity enthucutlet trying to live a more meaningful life, one step at a time.

Minute one: I can see energy gel packets, anti-chafing balm and smell coffee breath from pre-race jitters, rubber from thousands of shoe soles, sunscreen baking on skin, and the faint hint of yesterday's rain on Delhi’s streets. I hear the collective percussion of footfalls. Hundreds of runners finding their rhythm. Most of them about to press 'start' on their watches, breathless fragments of conversation, cheers from the sidelines, and the race announcer's voice fading behind me. Around me, a sea of colourful marathon T-shirts and race bibs moves as one organism. And I weave between pace groups, sidestep a runner adjusting her shoelace, and dodge the photographer crouching for the perfect shot.

This was me in a 10k run: heart pounding, lungs burning, and somehow, perfectly alive.

Until I was about 13 or 14, I would actively participate in my school's annual sports event at Gujarat Vidyapith. More than a dozen certificates chronicled my wins in 100-metre races. I represented my school in inter-school Kho-Kho tournaments. See, the thing is running wasn't something I did. It meant something to me. Until it didn't. I used to be extremely active at one point until one day I wasn't.

The transition happened so gradually that I barely noticed. A lot of what I used to enjoy felt like a waste of time in the grand calculus of career advancement. What good were endorphins when there were targets to hit? Why chase finish lines when I could chase goals? A classic product of the capitalist culture that I am.

"I'll get back to running and writing and drawing someday," became the lie I told myself as I surrendered my body to the altar of productivity - wolfing down junk food at my office desk, Red Bull coursing through my veins during all-nighters, and needing to vape every couple of hours (!)

January of 2023 is when it all changed. I had reached my breaking point. I was in the worst shape of my health (physical+mental). I quit my job.

Recovery from severe burnout isn't linear. Each day presented the same impossible question: how do you rebuild when the foundation itself is cracked? I fumbled to find a new rhythm as a freelancer while simultaneously trying to remember what it felt like to inhabit a body that wasn't perpetually exhausted.

Then came August 2023. I signed up for my first 3K. And that nearly killed me.

As I crossed that 3K finish line, gasping and stumbling: so bloody alive. The pain, the struggle, the burning in my lungs - it wasn't pretty, wasn't graceful, but it was real. More real than anything I'd felt in years. That raw, electric feeling of being fully present in my body again. That's what finally got me back to running again.

"In long-distance running, the only opponent you have to beat is yourself, the way you used to be," wrote Murakami in his brilliant book What I Talk About When I Talk About Running. "Most runners run not because they want to live longer, but because they want to live life to the fullest," he wrote.

I never fully understood the depth of that sentiment until November 2023, when the foothills of the Himalayas taught me what Murakami meant about fullness of life. One of my most interesting runs happened in that November in Kangra, Himachal Pradesh.

Kangra, Himachal Pradesh. Where clouds kiss ancient mountains and the air tastes like something precious you've forgotten.

I arrived with city lungs and city expectations. Ten kilometres - a distance I'd grown comfortable with on the predictable concrete of Delhi. "Just another 10K," I told myself. The first kilometre humbled me immediately. Trail running, I discovered, is a different language altogether. Here, each footfall is a negotiation and each breath a conversation with elevation. I walked when the mountain commanded it. I stumbled. I stopped to gasp at vistas that suddenly appeared through breaks in the forest: rewards that no city run could offer.

And this is exactly when the seed had been planted. A hunger for more wilderness, more challenge, more communion with terrain that demands everything you have. Somewhere in those Himalayan foothills, between gasps and missteps, the impossible idea took root: someday, I would run an ultra.

In one of my favourite films, Brittany Runs a Marathon, the protagonist speaks a truth that echoed through my mind as I navigated those trails: "I finally feel like I have control over my life, like I can trust myself again." Standing there, sweat-soaked, mud-splattered, and utterly humbled, I understood the paradox. Only by surrendering to something greater than myself could I reclaim the ability to trust my body again. Only by losing control could I find it.

Running outdoors isn't just exercise. It's a privilege. The freedom to move through open space, to feel wind against skin, to claim public territory with each footfall, especially in India where women's presence in public spaces has been contested and constrained for generations. This is a privilege I never take for granted, especially after learning about the women who fought through barriers so we could run freely today.

Consider Kamaljeet Sandhu in 19691.

Her final year of college would have been forgettable, another Indian woman preparing to disappear into domestic life. Instead, a physical education teacher scribbled her name for the 400-metre sprint at the National Open Athletics meet in Jalandhar. An afterthought. An experiment.

Kamaljeet had never run more than 200 metres in college events. The 400 was foreign territory, twice the distance, twice the pain threshold. Yet somehow, she found herself in the lead, her body moving with unexpected power.

Then, literally just 50 metres from glory, her legs betrayed her. They simply folded, like a building whose foundation had been quietly eroding. One moment racing, the next collapsed in a heap on the track.

The curious part? As she lay there, in her mind she was still sprinting toward the finish. The absurdity struck her, and she laughed out loud. A young woman sprawled on the track, laughing while officials rushed toward her with concern etched on their faces. Later, when coaches sought her out, embarrassment colored her cheeks. But that fall revealed something extraordinary. The commanding lead she'd established before collapsing caught everyone's attention. A diamond discovered through failure. This unlikely disaster put Kamaljeet firmly on the map for the 1970 Asian Games.

The morning of December 13, 1970, dawned in Bangkok with no hint of history about to be made. As Kamaljeet took her mark, India itself was mired in gloom. Political uncertainty in East Pakistan was building toward what would become the 1971 war and the violent birth of Bangladesh. In Bengal, Naxalite revolutionaries launched militant attacks on government targets. Jute mill workers demanded livable wages while the country's cotton stocks dwindled dangerously low.

Perhaps this darkness is precisely why what happened next burned so brightly in national memory. In 57.3 seconds, less than a minute of human effort, Kamaljeet Sandhu transformed from an athlete to an icon. The first Indian woman to claim gold in a running event at the Asian Games.

In a country where women's participation in sports was seen as cultural transgression rather than achievement, her victory cracked open a door that had been firmly shut. When The Times of India published its special edition in 1972, marking 25 years of independence, Kamaljeet stood as the only female athlete featured on the sports pages. The only other woman deemed newsworthy was Prime Minister Indira Gandhi herself.

That's how profoundly Kamaljeet's 57.3 seconds reshaped possibility, by proving that Indian womanhood and athletic greatness weren't mutually exclusive concepts. Her gold medal hung not just around her neck, but around the collective imagination of a generation of girls who suddenly had permission to run toward their own distant finish lines.

These days, there's a sacred rhythm to my running. Moments that have become as essential as the run itself. It begins with Murakami's voice, or rather, Ray Porter's voice bringing Murakami's words to life in my ears. I keep going back to my favourite parts from his audiobook What I Talk About When I Talk About Running (See, how I've referenced this same book twice in this essay. Well, that's precisely how central it's become to my running life.) Sometimes I catch myself nodding mid-stride, as though he and I are having a private conversation about why we subject ourselves to this beautiful punishment.

"All I do is keep on running in my own cozy, homemade void, my own nostalgic silence. And this is a pretty wonderful thing."

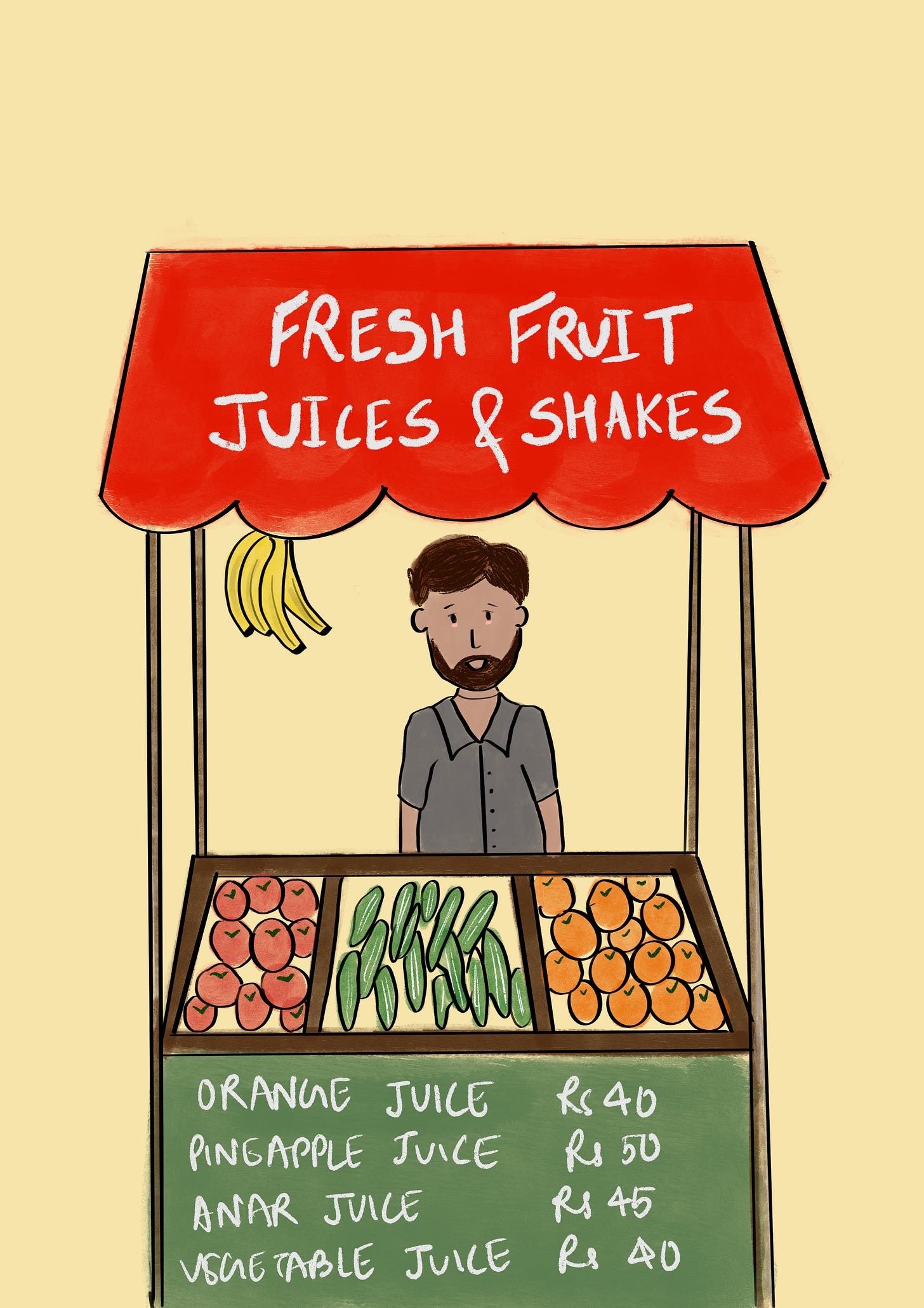

Other days, it's the encouraging cadence of a Nike Run Club guided run helping me with my breath, my pace, my thoughts - creating a different kind of meditation in motion. Once the run ends, there's Rahman ji's juice stand at the corner where sunlight breaks through buildings. He sees me approach, still flushed, still breathing heavily, and reaches for his vegetables before I even speak. The quiet choreography of his hands as they feed carrots, beetroot, and cucumber into the machine is what I look forward to watching. "Dhaniya nahi," he announces with a smile that suggests he very well remembers this small detail.

Can I call myself a runner yet? The question persists, despite the kms accumulated, despite the 6 am alarms I no longer snooze.

This year, the half marathon looms as both a challenge and a validation. Twenty-one kilometres that will somehow transform me into a runner. It will grant me the permission to claim the identity of a serious runner (what does that even mean).

Perhaps a runner isn't measured in distances or finish lines but in the rituals we build around the simple act of putting one foot in front of another. The way Murakami's reflections have become my companions. The way my body now craves movement instead of dreading it.

When I finally attempt the half marathon later this year, I won't be crossing some magical threshold that suddenly transforms me. I'll just be taking another step on a path that's already changing me. And I guess that's the gift running offers: not the certainty of arrival, but the humility of the journey. The understanding that we're always beginners in some way, always learning what our bodies and spirits can endure. The finish line, whenever I reach it, will just be another starting point. And Rahman ji's juice will taste all the sweeter for knowing how far I've come, and how far I have yet to go.

Kamaljeet Sandhu's inspiring journey was drawn from Sohini Chattopadhyay's illuminating book The Day I Became a Runner, which I absolutely loved reading.

Loved it, as usual. Posts like these would ideally help more folks to take up such activities because another corporate survivor just shared her struggles and joys of running. I'm not someone who likes to put strain on his body but have enjoyed running in the past with a personal best of 5k. Post that the physio politely asked me to stop doing it unless I wanted my partial ACL tear to evolve into a full tear. But I very vividly remember the feeling of completing 5k. You feel every heartbeat, your brain becomes quiet and the sense of accomplishment is just a cherry on top!

Thank you for making me relive my running story. Hope you achieve your running goals very soon :)

Best of luck for your half marathon. Really enjoyed this piece as a fellow runner.